Ordinary Objects, Extraordinary Stories

Ordinary Objects, Extraordinary Stories

By: Ziv Carmi, Stratford Hall Summer 2020 Intern

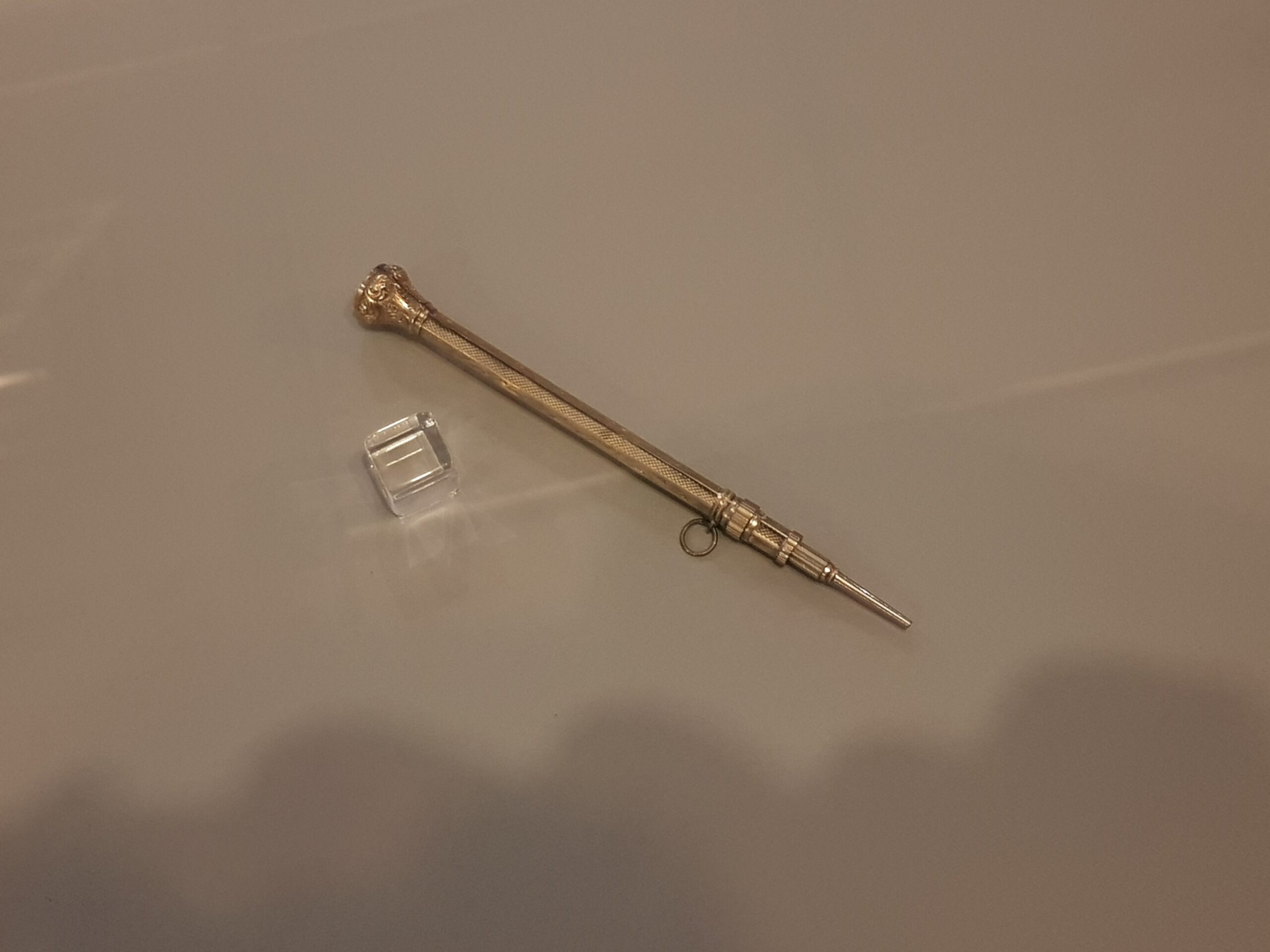

Today, the pencil is so ubiquitous that some may think it was always prominent in society. Oftentimes, the origins of everyday objects are overlooked. However, the five-century history of the pencil is fascinating, and this writing utensil, owned by Robert E. Lee, provides an opportunity to see what mechanical pencils looked like 150 years ago.

The story of the pencil begins in 16th century England when graphite was first discovered. It was cut into chunks and wrapped in paper or string and sold on the street.1 These tools were named “pencils”, from the Latin word pencillum, which means fine brush.2 Unlike quill pens, which were the writing tools of the time, there was no ink to spill and no ink to dry, making the pencil far more convenient. Sometime during the 1600s, a woodworker cut a stick in half, made a groove for the graphite, and glued the stick back together, creating the precursor to the modern-day wood pencil.3 These wood pencils were far studier than the paper or string pencils, and, for the first time, pencils could be sharpened using a blade.4

Due to England’s good quality graphite, the country became the leading producer of both pencils and graphite. However, by the 1790s, England’s domination of the pencil industry began to end. In 1793, Britain declared war against France, one of the largest importers of English pencils.5 This declaration of war resulted in a British embargo on France, which hurt both English commerce and the French pencil supply. The French Minister of War commissioned Nicolas-Jacques Conté to solve the pencil shortage and create a pencil that was not dependent on foreign materials.6 This meant either finding an alternative material to use or a mixture of graphite and another substance that would allow for the conservation of graphite. Conté’s solution consisted of a mixture of ground graphite and clay, which, when mixed with water, were put into rectangular molds and fired.7 Experimenting with this mixture, Conté found that he could make the pencil lead lighter or darker (and harder or softer) depending on how much clay he used.8 Furthermore, he cut a groove out of a stick and then glued the lead in, covering it with another piece of wood, which differed from the English method of making pencils.9 Conté’s pencil was patented in 1795 and became the basis of design for many future pencil manufacturers.10 Indeed, even today, pencils still utilize Conté’s graphite-clay mixture to create harder or softer pencil leads.11

With the rise of industry in the early 19th century came the rise of the machined pencil. Pencil companies in Germany and America began their rise, including Joseph Dixon’s company, which created the iconic Dixon Ticonderoga pencils that are still commonly used today.12 In 1858, Hymen Lipman glued a small piece of rubber to the end of the pencil, which is the first patented design of a pencil eraser (although the patent was ruled invalid in 1875 by courts).13 However, one of the most notable improvements to the modern pencil came in 1822.

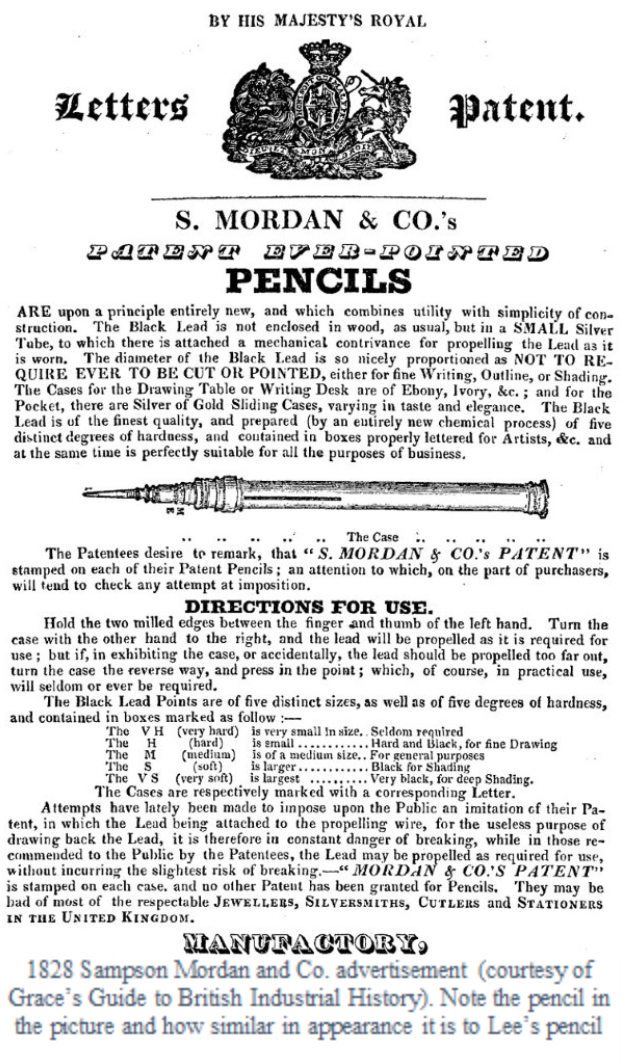

Patented in 1822, Sampson Mordan created the first mechanical pencil. Touted as the first “ever-pointed or propelling pencil”, Mordan’s pencils were advertised to never require sharpening.14 Unlike other pencils, which had the traditional wood casing around the lead, these pencils had lead inside a metal tube and used a mechanical apparatus to push the lead out.15

This particular pencil, owned by Robert E. Lee, looks very similar to the ones made by Sampson Mordan & Co and might have been manufactured by them. This mechanical pencil is gold and highly engraved, with a dark orange carnelian agate gem set in the top. There is an inscription near the top that says “Gen. R.E.L. from MCG”. Since the inscription refers to Lee as “General”, it was engraved either during or after the Civil War, as Lee left the American Army as a colonel. While it is not known exactly who “MCG” is, there is a distinct possibility that the pencil was given to Lee by Mary Catherine Goldsborough, a cousin of Mary Custis Lee, Robert’s beloved wife. Mary Goldsborough was the daughter of Robert Henry Goldsborough, a Senator from Maryland (1813-1818 and 1833-1836).16 Indeed, Goldsborough appears to have been close to the Lees, serving as a bridesmaid at Robert and Mary Custis’s wedding.17 She is also mentioned in several letters between Robert and Mary Lee as well, showing that she remained close to the couple after the wedding as well.18

Further evidence that gives credence to this conclusion was Goldsborough’s comparative wealth. A gold pencil would likely have been expensive, and only a person with reasonable wealth would have been able to afford it as a gift. While the 1860 census does not state her individual personal or real estate wealth, her brother William, who was the head of the household at the time, is listed as having a significant net worth, owning $66,000 in real estate and having $30,500 in personal estate value.19 Furthermore, in the 1870 census, Mary herself is listed as having $5000 in real estate value (about $100,000 today) while her family also has significant net worth, indicating that they were not rendered completely poor following the Civil War.20

As a mathematician and engineer, Lee likely used many pencils throughout his lifetime. Lee enrolled at the US Military Academy at West Point in 1825. While many now see West Point as a military school, it was the first, and at the time, foremost engineering school in the US.21 The curriculum consisted of advanced mathematics, chemistry, physics, and mineralogy, among others. In fact, these classes are all aspects of engineering programs today. The final term at West Point especially focused on engineering fortification, military architecture, and the science of artillery.22 Lee found much success and enjoyment pursuing these academic subjects. Indeed, his mathematical skills resulted in his promotion to acting assistant professor, a tutoring position, in his second year.23

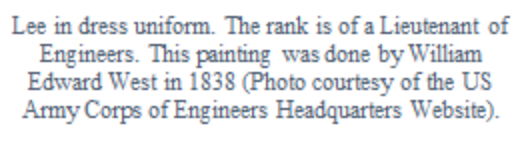

Lee graduated with high honors second in his class, entering the Army Corps of Engineers upon the receipt of his degree in 1829.24 Following his role in constructing several key forts along the East Coast, Lee was promoted in 1834 to assistant to the Army’s chief engineer.25 However, it soon became clear that Lee far preferred being in the field and doing construction work, so his superior officer assigned him to St. Louis, where he performed one of his most acclaimed feats of engineering.

Silt had built up, distancing the harbor at St. Louis from the deep water of the Mississippi River, and even created several islands that were blocking river traffic.26 Lee carefully surveyed and mapped the areas of issue, including nearby rapids that were equally dangerous for boats, before getting to work. As the mayor of St. Louis at the time, John Darby, said, “Lee simply changed the direction of the ‘Father of Rivers”.27 His system of dykes and dams moved the river back to its original location, washing the silt away and allowing boats to reach the harbor far more easily.28

Robert E. Lee is famous for his strategic genius in the Civil War, but few people are aware of his engineering prowess and love for drawing, both of which would have utilized pencils like this. Artifacts such as Lee’s mechanical pencil can tell us much about people in the past. Indeed, mundane objects like the pencil have their own fascinating histories, and, when studied, can show us how technology and society developed over time. In a museum setting, everyday objects like this pencil can help turn historical figures into more three-dimensional and complex figures. Robert E. Lee may be infamous for his role in the Civil War, but studying this pencil reminds us that he also had a lot of achievements away from the battlefield. Only by looking at the small things can we fully understand the everyday lives of these historical figures, and not just the large things that they are famous for, and thus, make sense of the past in an accurate and fair way.

See the pencil and more in the new exhibit, opening soon at Stratford Hall!

1 Schifman, Jonathan, “The Write Stuff: How the Humble Pencil Conquered The World,” August 16, 2016, https://www.popularmechanics.com/technology/a21567/history-of-the-pencil/

2Ibid.

3Ibid.

4Ibid.

5Ibid.

6Ibid.

7Ibid.

8Ibid.

Works Referenced

1860 United States Federal Census (Talbot County, Maryland). Accessed June 24, 2020.

1870 United States Federal Census (Talbot County, Maryland). Accessed June 24, 2020.

Clark, Jennifer. “Robert E. Lee’s Map of the Harbor of St. Louis.” September 21, 2016. https://www.nps.gov/jeff/blogs/robert-e-lees-map-of-the-harbor-of-st-louis.htm

Grace’s Guide to British Industrial History. “S. Mordan and Co.” Last edited April 24, 2019. https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/S._Mordan_and_Co

Lee Family Archives. “Letters, 1851-1860” https://leefamilyarchive.org/family-papers/letters/letters-1851-1860

Lee, Virginia Louise. “Robert E. Lee and His Children, Chapter IV: Marriage and Parenthood.” https://leefamilyarchive.org/reference/theses/vll/04.html

Schifman, Jonathan. “The Write Stuff: How the Humble Pencil Conquered The World.” August 16, 2016. https://www.popularmechanics.com/technology/a21567/history-of-the-pencil/

The Story of Ravensworth. “Goldsborough, Mary Caroline (1808-1890).” Accessed June 23, 2020. https://ravensworthstory.org/people/owners/goldsborough-m-c/

US Army Corps of Engineers Headquarters Website. “Historical Vignette 033- Robert E. Lee Served for 26 Years as an Officer.” August 2001. https://www.usace.army.mil/About/History/Historical-Vignettes/Military-Construction-Combat/033-Robert-E-Lee/

Weingardt, Richard G. “Robert E. Lee: Larger-than-Life Icon.” Leadership and Management in Engineering Vol. 13, Issue 3 (July 2013): 214-223. American Society of Civil Engineers.